Hiking Mauna Loa with Ellen and Seth

The Mauna Loa is the largest active volcano in the world. See what it's like to hike it bottom to top with Katadyn and Spectra Ambassadors, Seth and Ellen Leonard.

Most people, when I tell them I live on Hawai'i, think I sit around drinking Mai Tais on a beach backed by high-rises. First-time visitors sometimes think they can get around the island by bicycle. And those who saw last summer's news often ask with just a little schadenfreude if our house got run over by lava.

No, no, and no.

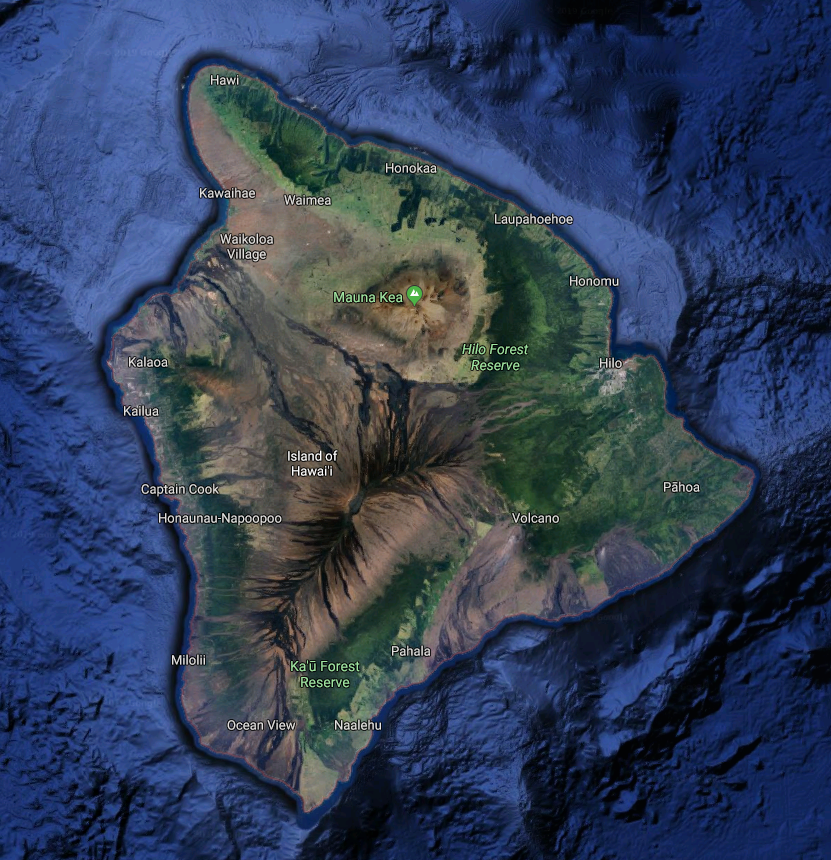

Honolulu is on O'ahu, a much smaller island northwest of Maui. Hawai'i, the Big Island, is a rural, sleepy place where residents are pretty much guaranteed to run into a friend anytime they go to the “big city” of Hilo, which arguably has more in common with Apia than Honolulu. Actually Apia, the capital city you've never heard of – it's in Samoa – has taller buildings than Hilo. While I do enjoy the occasional Mai Tai if there's a half-price happy hour somewhere, I'm more likely to be drinking water.

And no, you can't get around comfortably and easily on a bike. At least not if you're not the Kona Ironman World Champion. The island is huge, over 4,000 square miles. And mountainous. It's also incredibly ecologically diverse: you can go from tropical rainforest to Arctic tundra in a day.

Doing so means traveling uphill for nearly 14,000 feet from sea level to the summit of either Mauna Kea, the mountain that makes Hawai'i the second highest island in the world after New Guinea, or Mauna Loa, the only slightly smaller mountain to the south. Mauna Loa and the very active Kilauea Volcano below it, are the home of the Hawaiian volcano goddess Pele, who was extremely active last summer. Mauna Kea, which sees snowfall every winter, is the home of Poli'ahu, the snow goddess and enemy of Pele. Fortunately, I live on the flank of her mountain, not Pele's. So no lava yet. Mauna Kea is only dormant, though, not extinct.

Traditionally, only the high-ranking ali'i (chiefs) were allowed on the summits of these mountains. The true summit of Mauna Kea has a large cairn, decorated with votive offerings, and is a short climb from where the road to the astronomical observatories end. Those observatories have a fraught history, with the Hawaiian community divided between opposing them on the grounds that Mauna Kea is sacred land and supporting them on the grounds that Hawaiian culture is steeped in celestial exploration, the stars guiding their extremely skilled navigators on vast voyages across the Pacific.

The Mauna Loa summit cairn has far fewer votive offerings: by the shortest route, it's a 13-mile, 2,700-foot slog over loose, black lava. It's a brutal hike at high altitude under a dry, burning sun.

So, of course, my husband Seth and I decided to do it. It's not really that we're gluttons for punishment, but that we like uncrowded trails. Anything described in the trail guide as “big and wild, with little safety net” and a “slog over impossibly hard lava” probably wouldn't have many takers. There were also bold, large-font warnings about Acute Mountain Sickness, fast-changing weather, wintry conditions, and getting lost in fog.

While Mauna Loa isn't technically difficult – it's just a long, gradual hike – these warnings really should be taken seriously. The Long Mountain gets snow in winter; the wind can be fierce and gusty; and the barren lava fields are disorientingly similar if you lose sight of the ahu (cairns). And then there's altitude sickness.

Seth and I aren't exactly beginner hikers. Before moving to Hawai'i, we lived in the huge, steep, and glaciated Swiss Alps, very near to Mt Blanc. We ski-toured over the glaciers in winter and trekked all over the peaks in summer. In fact, we'd backpacked the whole length of the highest part, from Lake Geneva to Lake Maggiore in Italy, eschewing the hut network in favor of our own stink in our own tent, and choosing the highest, steepest trails. Our route had taken us over nearly 300 miles of rugged terrain and we'd gained and lost more than 35,200 meters – 115,600 feet (about 4 Everests) – over the whole thing. We aren't exactly strangers to altitude, either, regularly skiing above 12,000 feet with no problems.

Mauna Loa was probably the most brutal hike I've ever done. We made the mistake of going in early September. There was really no reason for this, and we knew better. It was just because we happened to be itching for a big hike, feeling nostalgic for our Swiss treks and craving a long, tiring day in cold fresh air. So we filled our daypacks with many liters of water (there's no water up there at all; you have to carry all of it), and set off before first light.

The sun is strong in the Tropics. And especially strong in summer. Between the spring and fall equinoxes, the sun is fairly well directly overhead. There are in fact two days in the year when the sun's “geographical position” is directly over the island of Hawai'i. Put another way, on those two days the earth is tilted so that the line of latitude on which Hawai'i falls is directly under the sun. A person (or anything else upright) will make no shadow at all at noon on those days. We summited Mauna Loa before the fall equinox, on a brilliantly clear day.

Of course, one wouldn't want anything other than a brilliantly clear day. For most of it, the “trail” isn't so much a trail as simply lava rock like all the rest of the lava spreading for miles and miles around. The only difference is that cairns have been built, showing the way. They are just far apart enough that if the fog rolled in, it wouldn't exactly be a challenge to lose the path.

We started off from the trailhead, at 11,000 feet, at an easy pace we could keep up all day and yet still make good progress. We were careful, taking frequent breaks for water and to look around and take pictures, not pushing our bodies. We knew we were out of practice with altitude. Except for the residents of Waimea and Volcano, at 3000 and 4000 feet, pretty much everyone on Hawai'i has no acclimation to altitude, one reason that the warnings about acute mountain sickness are so vehement. We live at 300 feet above sea level. In Switzerland we'd lived at 1300 feet, not a huge difference but something. We had also regularly climbed to 10,000 feet, so our bodies were much more acclimated. Before hiking Mauna Loa, we had spent the last six months almost entirely at sea level.

It takes about a week at altitude to truly acclimate. To do it right we should have been camping at five to seven thousand feet for the days leading up to our hike. That hadn't been feasible, so we were doing the only thing we could: taking it slow and drinking a whole lot of water.

We lingered at the big collapsed lava tube about a mile in, marked with two giant cairns. Soon afterwards we came to a small sign in the great expanses of billowy pahoehoe (the 'cake batter' type of lava) and spiky a'a (the sharp, angular type of lava). It informed us that we were entering the National Park, a place we hadn't been in months on account of the eruption of Kilauea. The trail became surprisingly trail-like for a bit, beaten down in lava crushed to tiny fine rocks, almost sand-like, with strands of shimmery gold: basaltic glass that's called Pele's hair. We took a long break at 12,600 feet, still feeling good but maybe just a tad more tired than we hoped we'd be.

At around 13,200 feet we reached the rim of Moku'aweoweo Crater, the enormous summit caldera created between 1000 and 1500 years ago when a huge eruption emptied out the summit magma chamber. The crater was a vast floor of deep black lava, silent and still beneath the white sun. It hasn't always been; Mauna Loa has had an active history of recent eruptions, right up until 1984 when the lava flows came within 4 miles of Hilo.

By that point we were both beginning to have mild headaches, but neither of us mentioned them. We were only 400 feet shy of the summit and, having lived in Switzerland so long, we'd acquired that Swiss emphasis on getting to the top.

But it was still 2.25 miles to make that 400 feet. For most of the way, we were out of sight of the caldera. The path also seemed to more than justify the “unforgiving” description in the trail guide of the jumbled a'a fields. I found it even harder on my joints than the granitic scree of the Alps above 10,000 feet.

We made the summit. Spread out beneath us was the entire, immense expanse of the caldera. A jet black floor against rusty red cliffs. It was like nothing I'd seen before, in its stark, vast, silent, unmoving, indifference. I'd seen the open ocean in its many moods, all of them indifferent to human presence. I'd seen the wide, white and blue crevassed carpets of glaciers, also indifferent. And I'd seen the brilliant red heaving mass of Kilauea's molten lava lake. But this was possibly even more awe-inspiring in all its silent desolation.

Seth and I signed the summit log and, as we were putting it away, a strange, loud whump came from close behind and to the right of us. We looked at each other with wide eyes, knowing Pele had hardly vacated Mauna Loa, that a 34-year hiatus in eruptions there did not mean she was finished with this huge, long mountain. We neither of us said anything, though. We were already there; there was nothing to say. Simultaneously, by mutual silent understanding, we started down.

We walked faster on the way down, our headaches building despite all the water we had drunk and were still drinking. The sun felt like a broiler despite the 50°F temperature as it beat down on our heads. We stopped for a snack at the turn-off back to our trailhead, the last point where we'd be able to see the huge caldera. I halfheartedly munched my trail mix; I didn't have much of an appetite.

By the time we reached the National Park sign again, we could see a thick blanket of fog rolling steadily up the saddle between Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa. It had already covered the 8,000-foot peak of Hualalai, the volcano above Kona. No guarantee it wouldn't creep higher and higher. The cairns were large, but they were also a little distance apart, and around them everything looked pretty much the same. We were walking fast now, faster than our bodies, obviously suffering mild altitude sickness, should really be pushing. Fear of being trapped and lost in the fog up there with the all-powerful goddess who creates and destroys at the same time, though, was sending us hurtling downhill. We reached the trailhead before the fog, but not before there was nausea in my stomach and pounding pain behind my eyes. The whole thing – 13 miles and 2,700 feet up and down – had taken us seven and a half hours, much longer than the same kind of mileage and elevation gain would ever have taken us in the Alps.

So why did Mauna Loa, if not defeat me, at least reduce me like that, when the Mont Blanc massif and the Klein Matterhorn never had? Maybe I'd intruded on Pele's domain and she was warning me. Or maybe it was just physiological. Living at sea level for six months and then climbing a 4000-meter peak? Not such a brilliant idea, and I knew that. Driving from sea level to the 11,000-foot trailhead in a couple of hours? That on its own would give many people altitude sickness, let alone a grueling hike under the tropic sun. And then that sun. No way around it; the sun and the desiccated air must have played a part. After all, in the Alps I could be atop a 10,000 or 12,000 foot mountain from my home at 1300 feet in under an hour during the ski season. But the sun in winter – and even in summer – at 46°N is very different from the sun at 19°N. The angle is lower and the UV index lower. I get headaches at sea level here on Hawai'i if I don't wear a hat. Of course I was wearing a hat on Mauna Loa, but it just wasn't enough.

Physiological or supernatural, Mauna Loa's effects were memorable. Most memorable, though, was the feeling of standing on that summit, overlooking the caldera. There just aren't words.

Words, Images by Ellen Leonard

Follow Ellen and Seth on their world adventures here: www.gonefloatabout.com

Instagram: @ellenandseth